In the original Final Fantasy, on the other hand, the rules of the world were not rules controlling complex movement as in Super Mario Brothers. The characters and their actions were representative, rather than direct. You moved your party all at once, indicated by a single iconic character figure, and the details of their progression over various terrain were of no consequence to the game. The rules of the game were instead limited to what terrain was passable, basic interaction with NPCs, including speech, trade, etc., and the complex mechanics governing combat. Each character class had its own path of development, endowing the character with the ability to cast new spells, perform new attacks, or deal greater damage.

Both of these examples, despite being drastically different styles of gameplay, are similar in that they are both directed narratives. In Super Mario Brothers, you move from left to right, with the only opportunities from deviation occurring when warp-zones are found. In Final Fantasy, the game state is advanced by talking to the right character, learning the next step, undertaking that specific step, and so on, repeated until the final boss is defeated. The path that the developer has created is the path to game completion. In Final Fantasy, you may have decided to create a party of all mages, but the overall story, who you speak to, and what you must do to progress, will essentially remain the same. There is, however, a separate class of gameplay that has become increasingly popular more recently. That is, the sandbox game type, which depends largely on the player to direct the narrative. The basic rules and elements are provided, as before, but the actual progression is an undirected emergence from the player's usage of those elements within the gameworld. In The Sims, for instance, the player is loosely directed by economic factors; find work and earn money to purchase new goods. However, the majority of short-term goals, conflicts, and enjoyable gameplay sequences occur as a result of the player's actions. Whether players were interested in actually building the house, or the interpersonal relationships that their characters developed, the majority of goals and actions were not directly scripted by the game designer. It is an act of trust on the part of the game designer that the rules they have created and the tools they have given the player will be suitable to allow the player to craft their own satisfying gameplay experience.

Logically, the ultimate promise of videogames would be the potential for an epic interactive narrative, one were the player is the main character in a vast, rich universe of their choosing. Unfortunately, this is generally not the case, as many of the games offering sandbox play are limited to more rudimentary interactions. For instance, you will never get to read a touching poem one of your characters in The Sims has written about their recently departed family member that you caused to starve to death by luring them into the bathroom and removing the door. Conversely, those games with the most well-developed narratives, including voice acting, clever writing, and plot twists, are generally the most heavily scripted by the game developer. The path to completion in a game such as Final Fantasy 12 is so heavily directed that the actual freedoms the player experiences are of almost no consequence to the story whatsoever.

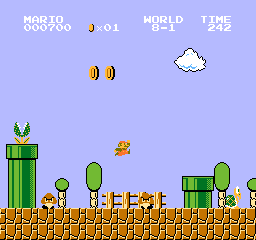

Inevitably, games are compared to movies and other less interactive forms of entertainment, and the argument is commonly made that the freedom and interaction games allow are what set them apart, but, as this Thinking Games blog post has argued, the scripted nature of many epic games makes them essentially the same. The gameworld is not a vast, functional universe. Instead, it is often a well-crafted facade, set up to appear open to the direction of the player. However, the actual opportunity to alter the experience is limited. Instead, many game developers are content to decide the entirety of the story and merely implement portions of the sandbox. Mario is a good example of this. The way you play out the given scenario on-screen is your own choice, but overall, you will progress in a linear fashion. Role playing games, by virtue of their very title, face an intrinsic conflict in design as they are, at their most basic, not meant to allow the player to deviate in their role in any way. The player serves as little more than a tool to increment the game state. Despite this, it is clear the ultimate goal of the RPG is to craft a fully realized universe in a box.

Trends in RPG development bear this out, and the movement towards ever more comprehensive gameworlds illustrates the inherent conflict. Oblivion, for instance, strives to create the feel of the sandbox, the utterly open world with which the player can do as they see fit, while also populating the world with a wide range of characters that interact in sophisticated ways. Unlike a movie, the goal of a game such as Oblivion is to give the player the power to be the star, but the reality of the game falls short. In fact, infinite play-throughs of Oblivion will not yield infinite outcomes. To satisfy the feeling of choice, the characters are given a wider range of scripted responses, allowing some variability, but the player is still ultimately limited to the paths the developer has chosen. The outcomes of the various quests and the results of conversations with NPCs will never deviate from these paths, except where the player has managed to break the game.

So will videogames ever manage to successfully create a complete world for the player to retreat to, while still maintaining a level of complexity that will allow the interactions to deliver the sort of dramatic impact that a movie like Star Wars has? That would be the holy grail of game development. It is my belief that sandbox games are a step in the right direction. As they develop in sophistication, the lexicon of meaningful interactions increase. The range of actions and responses that the self-motivated characters within a given sandbox game can make will continue to increase until they are very close to approximating the scripted actions of a linear narrative game. In the meantime, we have plenty of MMOs in which the other characters are actual humans. It is unfortunate that the quest direction, over-arcing story, and enemies are generally computer-controlled, but that is a topic for another column.

No comments:

Post a Comment