Maybe Little King's Story should have been rated M by the ESRB, because it is through mature eyes that Cing and Xseed's unique strategy adventure was certainly meant to be viewed. Behind the childlike veneer of bright, cutesy graphics, classical music, and simple gameplay mechanics lies a sophisticated game about imperialism, authority, greed, excess, self-loathing, gender roles, and other social dynamics. This game is not for children, as its colorful store-shelf appearance may suggest to consumers, but it is a highly playable and very enjoyable experience for more discerning Wii owners.

In Little King's Story, the player assumes the role of a new king in a strange, whimsical, fairytale land. The main goal is to expand the kingdom of Alpoko by amassing citizens, training each in one of many different occupations, and using them to venture into uncharted territories and conquer the eight other kings in the world. This foreign policy is of course heavily influenced by the king's ambitious advisor, who at times during cutscene conversation will slip and hint at his selfish motivation. The king's imperialistic goal is at once described as both "world unification" and the much less flowery "world domination." Either way, the player's objective is the same -- explore and take over the entire world.

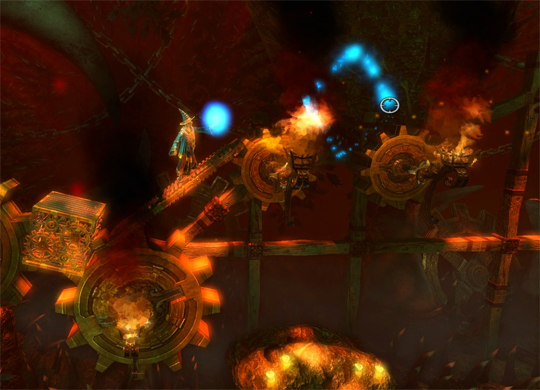

Gameplay is reminiscent of titles like Pikmin and Overlord, where the player directly controls a single leader and issues simple commands to the small entourage that trails like a group of ducklings. Little King's Story adds depth to this premise by combining more traditional real-time strategy components with the basic charge-or-retreat mechanics of those games. Players will collect items throughout the land by defeating enemies or searching through various aspects of the environment (pots, holes, fallen logs, stones, etc.), and then take them to the castle to be exchanged for money. The king can use this money to initiate "Kingdom Plans," which are mostly projects to build citizen-generating residences or job-training facilities that will convert the "carefree adult" base units into specific job classes. Other kingdom plans include power-ups that improve citizen health, increase the size of the king's "Royal Guard," or allow the group to be arranged in different formations in the field.

The game features nearly 20 unique job classes, ranging from the hole-digging farmer to highly specialized units like the wizard and doctor. Each job is vital to the king's campaign -- carpenters build bridges, miners break through stone, lumberjacks cut down trees, soldiers fight battles... -- and he can take only a set number with him each time he ventures outside the kingdom's borders, so the Royal Guard will constantly change throughout the adventure, consisting of different combinations of citizens all the time.

The citizens of Alpoko all have names, personalities, and individual lives that play second fiddle to the will of the king. These folks may cultivate friendships with one another, fall in love, marry, have children, and even mourn the deaths of other members of their personal social circles (based on the communities in which they live and the members of the Royal Guard teams they are parts of). This is quite different from similar games, where the nameless peons seem to be entirely expendable, and players feel no connection with what is essentially just another group of tools. Here, players learn their citizens' names, watch relationships flourish, and may even feel some remorse when they die.

Being pulled from their comfortable lives to serve in the Royal Guard will often elicit complaints from citizens, but they will inevitably acquiesce to the king... and the good of the kingdom. While a part of the king's Royal Guard, citizens do just as they're ordered, but it's interesting to see how the members of certain occupations will behave if left to their own artificially intelligent devices. For example, the game describes the top infantry units, hardened soldiers, using the phrase, "All they know is violence." Indeed, not only are these meatheads useless for any constructive task (all they can do is fight or break things, including the fine craftsmanship of the kingdom's royal carpenters), but they also harass and push around Alpoko's carefree adults when they are not under the king's direct command.

Other citizens have quirks as well. Kampell, the 'prophet' to the god Ramen makes ridiculous claims about faith and prayer, citing his obviously fictional deity as the cause and effect of everything in the world. Conversely, the answer-seeking cosmologist Skinny Ray exhibits his paranoia about unexplained natural phenomena with wildly inductive, pseudo-scientific conclusions. The humor and candor with which Little King's Story's world is presented is refreshing and entertaining, and along with its mild visual stylings, compliments the more serious nature of the game's messages.

This game is crammed full of both the expression and criticism of many different societal views and beliefs. Within Alpoko, one might notice that only after building a church can citizens consecrate their love (via the player sending the couple into the institution together), and only after marrying will they have a child. However, the trend is most clearly evident in the characterization of the other kings and their followers. For example, one king preaches peace and love, but he and his citizens exist in a perennial drunken (and particularly violent) stupor, applauding the behavior all the while. Another kingdom is practically MADE out of culinary delights, and the king does little more than ceaselessly indulge. There is a kingdom where television is idolized, and others where pride or worry consume the people's lives. Each kingdom seems to have at least minor ties with some real-word counterpart, highlighting a specific aspect of the culture there. Even the nonsensical voices of the characters lean audibly toward a specific real-world language in each kingdom.

According to game director Yoshiro Kimura, under the actual gameplay, Little King's Story is an exploration of what it means to be noble, and whose sets of values are the most noble of them all. This game is as much about its words as its gameplay, and conversations with the other kings, letters from citizens, and the menus themselves combine with the game's imagery to deliver many of its messages. But this is still something that is meant to be played... and it does that fairly well.

While members of Royal Guard can get hung up on buildings, fences, and other obstacles fairly easily (navigating stairs is a daunting challenge until players acquire the single-file "evade" formation), and it is sometimes difficult to maintain a bead on targets with the loose lock-on system, running around the kingdom and directing the king's forces is relatively painless and enjoyable. Commands to charge, retreat, line up according to job, change formation, disband, and adjust camera angle are all housed on the Wii remote, with map, movement, and the king's piddly wand attack on the nunchuk. There are absolutely no motion controls involved, and I never found myself searching for such input methods. Other than the inability to split forces or temporarily dismiss a part of the group -- options that would make performing tasks and fighting battles less unnecessarily difficult -- there is little more to ask of the control scheme.

Little King's Story is one of the best in the Wii's library. It is fun to play for hours on end, and offers much more depth than your average title. It has a look all its own and the highly recognizable classical music is used very well. If you're looking for something good on the Wii, I recommend that everyone at least give Little King's Story a try.